CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

DISCUSSION:

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema (NME) is seen in paraneoplastic syndromes resulting from gastroenteropancreatic tumors. The most common tumor associated with NME is a glucagonoma. It is usually a single, large and slow-growing tumor found in the body or tail of the pancreas. Affecting the islet cells of the pancreas, various peptides (somatostatin, insulin, gastrin) are synthesized and secreted. In each case, the common link is hyperglucagonemia. It may be seen as part of MEN 1 and more than 75 percent have metastasized at the time of diagnosis. Metastases predominate in the liver and bone tissue.

Manifestations of glucagonoma syndrome include dermatitis, glossitis, stomatitis, angular cheilitis, anemia, and weight loss. There may also be associated with psychiatric disturbances. Occasionally, cutaneous lesions are the earliest signs. Malabsorption and diarrhea lead to deficiencies of essential fatty acids, zinc, and amino acids. A fasting glucagon level > 1,000 ng/L establishes the diagnosis. The high levels of glucagon are responsible for most of the observed signs and symptoms.

NME is the characteristic skin manifestation of glucagonoma syndrome. It may also be seen in hepatic cirrhosis, a jejunal adenocarcinoma, and malabsorption syndromes. It appears in periorificial, flexural, and acral areas in addition to the perineum. Lesions may begin as coalescing papulovesicles that erode and crust in circinate patterns. Rapid healing and development of new lesions result in daily fluctuations of the eruption. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may be evident.

TREATMENT:

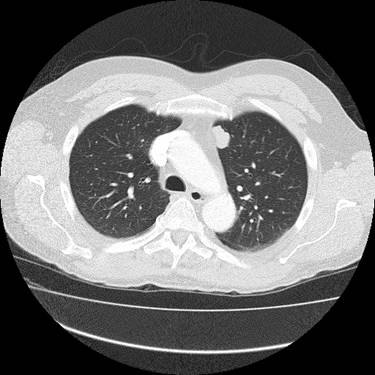

The actual treatment for this patient: The groin outbreak cleared subsequently with application of a mixture of nystatin, hydrocortisone cream, and zinc oxide. Facial and scalp lesions were controlled with topical steroids and antifungals. Because of the extensive visceral involvement, the patient was referred to Hematology/Oncology. The patient began a regimen of alternating streptozocin and adriamycin. Repeat imaging after two cycles revealed stabilization of the pancreatic and liver masses and near normalization of glucagon levels. Psychiatric medications were continued.

Other Treatment Options: Surgical debulking may lead to resolution and cure if the syndrome is diagnosed early enough. Supplementation with amino acids and essential fatty acids is helpful in rare cases. Palliation is achieved with chemotherapy, somatostatin infusions, and hepatic artery embolization.

REFERENCES:

Chastain, M. A. (2001). The glucagonoma syndrome: A review of its features and discussion of new perspectives. American Journal of Medical Sciences, 321(5), 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200105000-00007 [PMID: 11314812]

Fauci, A. S. (1998). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (14th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Freedburg, I. M. (1999). Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Odom, R. B. (2000). Andrews’ diseases of the skin (9th ed.). W.B. Saunders.

Wermers, R. A. (1996). The glucagonoma syndrome: Clinical and pathological features in 21 patients. Medicine, 75(2), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-199603000-00002 [PMID: 8640361]