CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome

DISCUSSION:

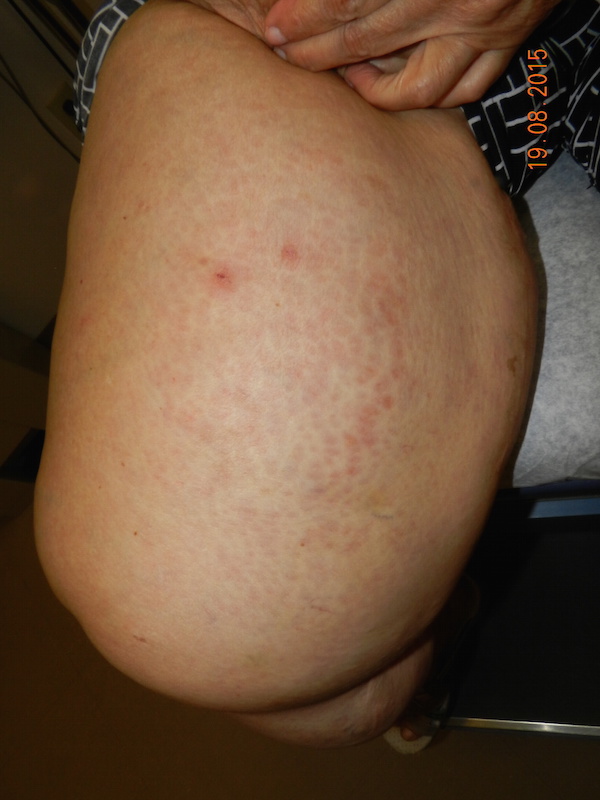

Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome (MLNS) or Kawasaki Syndrome is a syndrome usually affecting infants and children 390 C, associated with lethargy, irritability, and occasional colicky abdominal pain. Usually within a day of fever onset diffuse erythema and a polymorphous eruption that is morbilliform, urticarial, scarlitiniform, targetoid, or annular appears. This is followed within several days by mucous membrane changes including erythema, swelling, and fissuring of the lips, strawberry tongue, erythema of the pharynx, and nonexudative bilateral conjunctival injection.

The most characteristic changes occur during the first week in the distal extremities when proximal leukonychia partialis occurs. Beginning about day 4 or 5 painful induration with taught non-pitting edema of the hands and feet, polyarticular arthritis and arthralgias (30%) appear. Then on about the 10th to 21st day periungual, palmer, and plantar desquamation begins, sometimes sluffing in large casts revealing new, normal skin. Cervical lymphadenopathy is present throughout the course. The illness may last for 2 to 12 weeks or longer and relapses may occur.

The most concerning complications, those related to the heart, occur during the sub-acute phase beginning about the 10th day as the eruption, fever, and other early clinical signs begin to subside. At this time inflammation of the coronary arteries may result in coronary artery aneurysms (5 to 20%), pericardial effusion (12 to 30%), pericarditis, myocarditis, cardiac tamponade, and arrhythmias (due to ischemia, CHF, and mitral valve involvement). Other reported clinical findings include but are not limited to pneumonia, aseptic meningitis, diarrhea, tympanitis, petechial or vesicular exanthems, tonsillar exudate, encephalopathy, acute distention of the gallbladder, anterior uveitis, pleural effusion, and hepatitis.

Laboratory findings are variable and are associative at best and may not be used as inclusion/exclusion criteria. During the acute phase of disease leukocytosis with a marked elevation in immature (band) cells occurs. During the 3rd and 4th weeks of illness marked and nearly universal thrombocytosis (>500,000/ul) develops. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia particularly IgE, with mild elevation of serum transaminases and complement are also seen. Depending on the organ system involved other laboratory abnormalities may be observed and include: normochromic normocytic anemia, elevated sedimentation rate, and acute phase reactants, decreased albumin, sterile pyuria, mild proteinuria, CSF mononuclear pleocytosis with normal glucose and protein, ECG changes such as arrhythmias, LVH, or decreased voltage. Echocardiography can detect coronary artery aneurysms at about the 5th week and is useful in all cases.

Diagnosis is based upon exclusion and clinical findings. Fever of at least 5 days duration and the presence of at least 4 of the following physical presentations: bilateral nonexudative conjunctival injection; changes in the lips, tongue and oral, mucosa such as injections; cervical lymphadenopathy >1.5cm; polymorphous truncal exanthem; and, changes in the peripheral extremities such as nonpitting edema, erythema, and desquamation. Note that there are children with atypical illnesses who do not meet diagnostic criteria and develop coronary artery aneurysms.

The overall mortality is estimated at 1 to 2% and is most often related to cardiac complications. Mortality is highly unpredictable; > 50% of deaths occur during the 1st month, 75% within 2 mo, and 95% within 6 mo. However, death has been reported 10 years later and can be sudden and unexpected. If no coronary artery disease can be demonstrated during follow up, the prognosis is excellent and complete recovery is the norm. Even those with demonstrated aneurysms tend to show echocardiographic evidence of regression within 1 yr, although it is not known if residual vascular damage remains.

TREATMENT:

The current standard and the actual treatment for this patient are the same and included Intravenous gamma globulin (IVGG) as the mainstay for therapy. Doses of 400mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days, or as a single dose of 2mg/kg may be administered. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin is also recommended; dipyridamole is used as an alternative for patients unable to take aspirin.

This approach reduces the prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities from 20%, for those treated with aspirin alone, to 4%. Angioplasty, thrombolytic therapy, or CABG surgery may be required for patients with severe disease.

REFERENCES:

Nakamura, Y., et al. (1998). Mortality among patients with a history of Kawasaki disease. Acta Paediatrica (Japan), 40, 419. [PMID: 9649561]

Yangawa, H., et al. (1998). Results of the nationwide epidemiologic survey of Kawasaki disease in 1995 and 1996 in Japan. Pediatrics, 102(E65). [PMID: 9682990]

Arndt, K. A., et al. (1996). Cutaneous medicine and surgery: An integrated program in dermatology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company.

Odom, R. B., et al. (2000). Andrews’ diseases of the skin. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company.

Shelly, W., & Shelly, D. (2001). Advanced dermatologic therapy 2. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company.

Habif, T., et al. (2000). Clinical dermatology: A color guide to diagnosis and therapy (3rd ed.). St. Louis: The Mosby Company.

Fitzpatrick, T. B., et al. (1993). Dermatology in general medicine (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.