CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Alopecia syphilitica of secondary syphilis

DISCUSSION:

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema Pallidum and if left untreated, it is a chronic, systemic infection that progresses through early (primary and secondary) and latent stages. Secondary syphilis develops after hematogeneous and lymphatic dissemination of the microorganism, typically 3-10 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. Circulating immune complexes of treponemal outer membrane proteins, human fibronectin, antibodies, and complement play a role in the pathogenesis of the many clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis(2).

Secondary syphilis is characterized by mucocutaneous and systemic manifestations. The most commonly observed is a generalized, non-pruritic papulosquamous exanthem that includes the palms and soles and may have a collarette of scale and condylomata lata in the genital and anal area. Manifestations may also occur on mucous membranes and scalp (2).

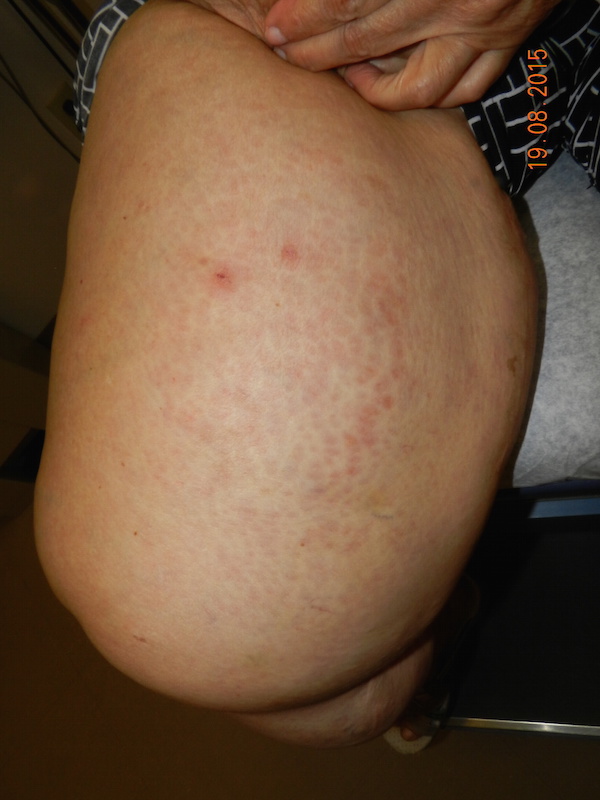

Alopecia can occur on its own as “essential syphilitic alopecia” or in combination with other symptoms of secondary syphilis as “symptomatic syphilitic alopecia”. It appears on the scalp as a patchy “moth-eaten” appearance, a diffuse pattern, or a combination of both. While it most commonly involves the scalp, it may affect other places of hair growth, such as the eyebrows, eyelashes, chest, legs, axilla, or pubis. The lesions are non-inflammatory and non-scarring(1).

Histopathologic features of alopecia syphilitica have not yet been established due to the limited number of biopsies available in the literature. However, a common characteristic is perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate. The other pathologic changes closely resemble those seen in alopecia areata, but the sparse plasma cell infiltrate and absence of small or abnormal anagen hair follicles in alopecia syphilitica can aid in distinguishing the two (1). One case report exists in the literature in which the detection of T. pallidum occurred in the hair follicle (4).

The diagnosis of syphilis is based on either direct detection of treponemes or treponemal DNA or serologic tests that assess antibody response to cardiolipin (non-treponemal) or treponemal antigens. Direct detection must be made by microscopic examination because T. pallidum cannot be cultured in vitro and definite diagnosis can be made by darkfield microscopy. Non-treponemal tests, such as the RPR, are used qualitatively for screening purposes and quantitatively by an antibody titer to provide a baseline for follow-up evaluation after antibiotic therapy. Treponemal tests, such as the FTA-ABS, are used for confirmation of a reactive non-treponemal test. These tests remain positive indefinitely, and therefore quantitative evaluation is not necessary. The specificity is high, and the sensitivity is 100% in secondary syphilis (2).

The subtleness of symptoms and signs and mimicry of other diseases are hallmarks of secondary syphilis. Therefore it is important that alopecia syphilitica be considered in the differential diagnosis of patchy hair loss.

TREATMENT:

The primary treatment for syphilis is a single intramuscular dose of 2.4 million units Penicillin G benzathine. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, alternative therapy includes doxycycline 100mg bid x 14 days or tetracycline 500mg qid x 14 days or ceftriaxone 1 g daily IM/IV x 8-10 days. For patients with latent syphilis (>1 year duration), unknown duration, cardiac involvement, or tertiary syphilis, 2.4 million units IM benzathine penicillin should be given weekly x 3 weeks (5). Follow up serologic testing is recommended at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months following antibiotic treatment, then every 6 months for up to 2 years post-treatment. Treatment may vary with HIV status of the patient or the presence of neurosyphilis, and the CDC should be contacted for support (2). Alopecia usually resolves within 3 months of treatment (1).

REFERENCES:

B.i, M. Y., Cohen, P. R., Robinson, F. W., & Gray, J. M. (2009). Alopecia syphilitica: Report of a patient with secondary syphilis presenting as moth-eaten alopecia and a review of its common mimickers. Dermatology Online Journal, 15(10), 6. https://doi.org/10.5070/D15d10

Bolognia, J., Jorizzo, J., & Rapini, R. (2008). Dermatology. Mosby.

Arizona Department of Health Services, Sexually Transmitted Disease Program. (2009). Annual report 2008 (Updated May 22, 2009). pp. 1-31.

Nam-Cha, S. H., Guhl, G., Fernandez-Pena, P., & Fraga, J. (2007). Alopecia syphilitica with detection of Treponema pallidum in the hair follicle. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology, 34, 37-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00524.x [PMID: 17140489]

Nusbaum, M., Wallace, R., Slatt, L., & Kondrad, E. (2004). Sexually transmitted infections and increased risk of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 104(12), 527-535. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2004.104.12.527