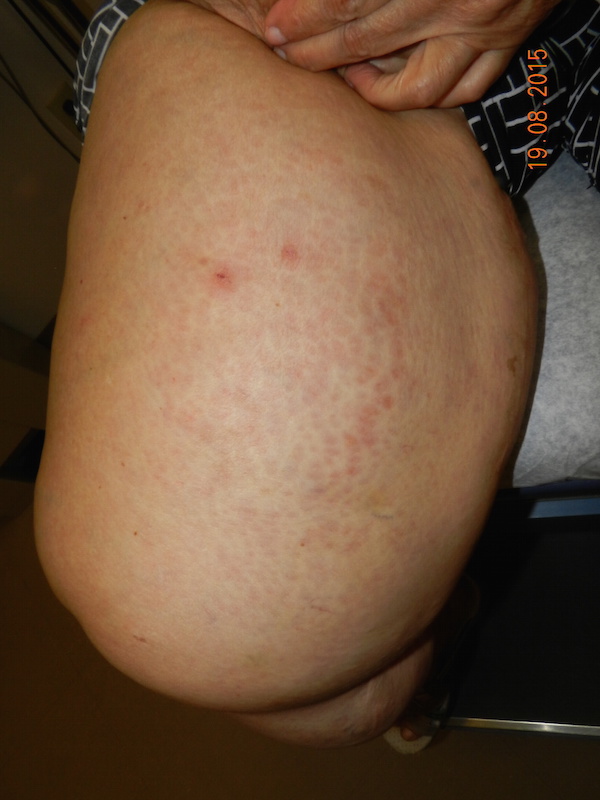

CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Eruptive Xanthoma

DISCUSSION:

Xanthomas are deposits of lipids in the skin and sometimes of the subcutaneous tissue that are expressed clinically as yellowish to erythematous papules and plaques.1 The lipid deposits in xanthomas are thought to be derived from circulating plasma lipoproteins.3 In many cases, this condition is secondary to a metabolic condition, such as hyperlipidemia, but not in all cases. It is important to determine if there is underlying hyperlipidemia, as this can lead to atherosclerotic disease attributing to severe morbidity and mortality. It is also important to assess the cause of hyperlipidemia, as it may be a manifestation of other systemic diseases. Some common conditions that can lead to hyperlipidemia include diabetes, obstructive liver disease, thyroid disease, renal disease, and pancreatitis. If recognized and treated early enough, progression to atherosclerotic disease and/or pancreatitis may be prevented, as well as the resolution of the xanthomas.2

Eruptive xanthomas are often the result of elevated serum triglyceride levels. They present in a disseminated manner, with a predilection for the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the thighs and arms, knees, intertriginous areas, and oral mucosa. Pruritus is variable but is often severe and the presenting complaint of the outbreak.9 Hypertriglyceridemia levels associated with eruptive xanthoma often exceed levels of 3,000-4,000 mg/dL.7 When levels these high are achieved, one must consider the possibility that there is an associated HLP. Table 1 demonstrates the five different types of HLPs.

In addition to hyperlipidemia, certain medications have been shown to cause eruptive xanthomas. The most common inciting medications to cause eruptive xanthomas to include systemic estrogens, systemic corticosteroids, systemic retinoids, and olanzapine.5,9

Other forms of xanthomas include tuberous/tuberoeruptive xanthomas, tendinous xanthomas, plane xanthomas, and verruciform xanthomas. Tuberous/tuberoeruptive xanthomas are described as being pink-yellow papules or nodules, most commonly found on the extensor surfaces, most notably on the elbows and knees. These lesions are usually seen in individuals with elevated serum cholesterol. Similar to eruptive xanthomas, tuberous/tuberoeruptive xanthomas are often associated with a HLP, most commonly types II and III.7 Tendinous xanthomas are described as being firm, smooth deposits of lipid that affect the Achilles tendon, as well as extensor tendons of the hand, knees or elbows. These lesions are also closely associated with types II and III HLP.7 Plane xanthomas are described as being orange-yellow macules, papules, patches, and plaques. Plane xanthoma location is often predictive of an underlying disease. For example, lesions in intertriginous areas are suggestive of type II HLP.7,10 Lesions located within palmar creases (xanthoma striatum palmare) suggests type III HLP.7 Xanthalasma (xanthelasma palpebrarum) are plane xanthomas of the eyelids. While about half of these patients have underlying hyperlipidemia, the presence of these lesions is not pathognomonic for such conditions. Plane xanthomas in the setting of a normolipidemic individual raise the concern of an underlying monoclonal gammopathy, including multiple myeloma, B-cell lymphoma or Castleman’s disease.7 Verruciform xanthomas are typically solitary lesions that average 1-2 cm in diameter. These lesions usually arise in and around the mouth or in the anogenital region. Unlike the other forms of xanthomas, verruciform xanthomas are not associated with underlying hyperlipidemic states. Verrucform xanthomas are often found in the presence of other disease states, such as lymphedema, epidermolysis bullosa, graft-verse-host disease, and CHILD syndrome.7 Table 1 demonstrates the different HLPs and the form of xanthomas that are commonly associated with each.

TREATMENT:

Treatment of eruptive xanthomas is directed at lowering the serum triglyceride levels. An overview of the patient medication list will show if an offending agent is being used and if so it should be stopped or switched to an alternative medication that is not known to trigger eruptive xanthomas. Well balanced diet and exercise are the cornerstone for lipid-lowering techniques; however, in most cases, this is not enough to normalize the extremely elevated triglyceride levels that are associated with eruptive xanthomas. The best medications for lowering serum triglycerides specifically are the fibric acid derivatives (fibrates) and omega-3 fatty acids.8 The fibrates decrease VLDL synthesis and increase lipoprotein lipase LPL which aid in lowering serum triglyceride levels. Omega-3 fatty acids increase triglyceride catabolism, which also aids in lowering serum triglyceride levels.8 Failure to treat the extremely elevated serum triglyceride levels that are associated with eruptive xanthomas can lead to a more serious sequel, including pancreatitis and atherosclerosis.7 Once serum triglyceride levels approach reasonable levels, not only does the risk of pancreatitis and atherosclerosis decease, but the cutaneous lesions also will resolve over several days to weeks.7 In addition to oral medications, other treatment modalities have been described for lesions resistant to contemporary medical treatment options. Surgery, lasers, and cryotherapy are the most commonly used of these alternative treatment options.6

REFERENCES:

1. Lugo-Somolinos A, Sanchez JE. Xanthomas: a marker for hyperlipidemias. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2003 Jul-Aug; 95(4): 12-6.

2. Parker F. Xanthomas and hyperlipidemias. J Am Acad Dermaol. 1985 Jul; 13(1): 1-30.

3. Parker F, Bagdade J, Odland G, Bierman E. Evidence for the chylomicron origin of lipds accumulating in diabetic eruptive xanthomas: a correlative lipid biochemical, histochemical, and electron microscopic study. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1970 July; 49

4. Nayak K, Daly R. Eruptive xanthomas associated with hypertriglyceridemia and new-onset diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2004 March; 350: 1235

5. Chang HY, Ridky TW, Kimball AB, Hughes E, Oro AE. Eruptive xanthomas associated with olanzapine use. Arch Dermaol. 2003 Aug; 139(8): 1045-8

6. Zaremba J, Zaczkiewicz A, Placek W. Eruptive xanthoma. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013 Dec; 30(6): 399-402

7. Bolognia, J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer J. Xanthomas. In: Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012: 1411-19

8. Rader DJ, Hobbs HH. Disorders in Lipoprotein Metabolism. Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, Braunwald E, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012: 3145.

9. James W, Berger T, Elston D. Errors in metabolism. In: Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2011: 520-525

10. SethuramanG, Thappa DM, Karthikeyan K. Intertriginous xanthomas – a marker of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:338.

Additional Comment: Cutaneous lesions are often the initial finding in otherwise systemic disease processes, placing the dermatologist in a position of great importance in relation to disease prevention and management.