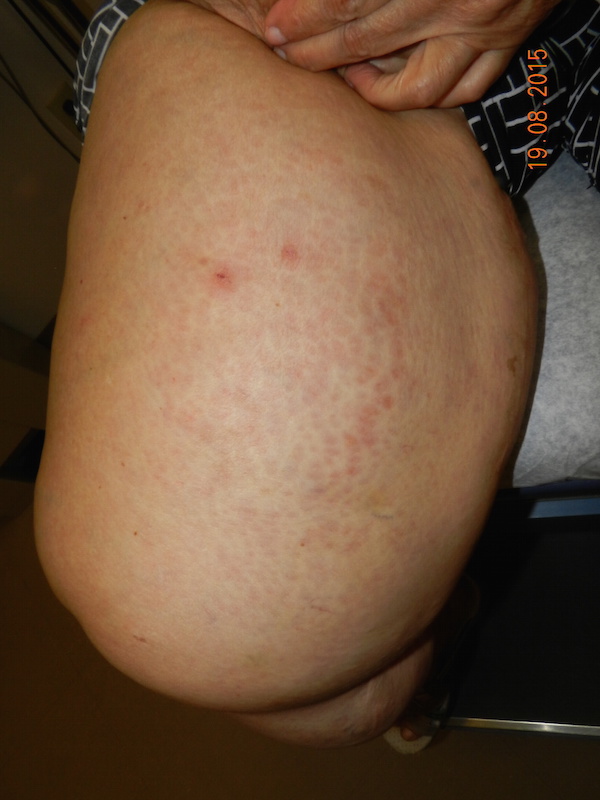

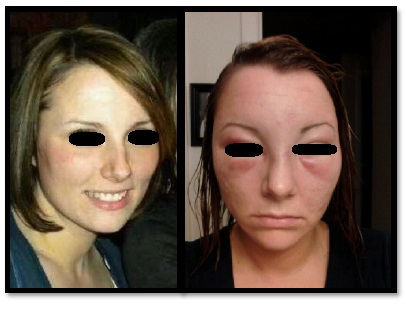

CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Early Anetoderma

DISCUSSION:

Anetoderma is characterized by focal elastolysis, resulting in well-circumscribed macules, papules, and/or depressed lesions. It is generally classified as either primary when it arises within normal skin, or secondary when it arises in the setting of a wide variety of underlying cutaneous and systemic disorders. (1)

Primary anetoderma is further divided into the Jadassohn-Pellizzari type, which is preceded by inflammatory lesions, and the Schweninger-Buzzi type, which is not associated with clinical inflammation. These forms typically occur in young adults with a female preponderance. Secondary anetoderma may occur in association with a primary inflammatory dermatosis (e.g. sarcoidosis), cutaneous tumor, skin, or systemic infection (e.g. borreliosis, HIV, syphilis), autoimmune disease, or drugs (penicillamine). Most notable in this case are correlations with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and Graves’ disease. Familial and neonatal forms of anetoderma have also been described.

The pathogenesis of anetoderma is unclear. Loss of dermal elastin may be mediated by inflammatory factors such as cytokine activation, phagocytosis, and release of elastase and progelatinase. Macrophage activity may be particularly key in explaining the connection between secondary anetoderma and autoimmune disease. (2,3)

Treatment options for anetoderma have proven largely unsuccessful thus far, and lesions do not typically spontaneously regress. These include intralesional corticosteroids, aspirin, dapsone, phenytoin, penicillin G, vitamin E, niacin, aminocaproic acid, and cryotherapy. Partial responses have been achieved with hydroxychloroquine and colchicine. Surgical excision may be considered in cases of limited involvement. Three recent studies have reported clinical and histopathological improvement using laser therapy as an alternative treatment modality. (4,5,6)

TREATMENT:

After establishing the diagnosis, the patient was sent for laboratory screening to evaluate for potential secondary causes. Ordered TSH, ANA with reflex, and anti-phospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, and anti-beta-2 microglobulin). All of these studies returned as unremarkable, ruling against an autoimmune etiology.

Given the extent of involved skin in this patient, excision was not a feasible treatment option, and she preferred to attempt conservative management prior to starting any oral medication. The patient has agreed to undergo a trial of 1540 nm non-ablative fractionated laser therapy on a 4 cm square test area, with 3 passes, for 3 treatments spaced 3-4 weeks apart.

REFERENCES:

Maari, C., & Powell, J. (2012). Atrophies of connective tissue. In Bolognia, J.L., Jorizzo, J.L., & Schaffer, J.V. (Eds.), Dermatology (Vol. 2, pp. 1632-1635). Amsterdam: Elsevier Limited.

Kineston, D.P., Xia, Y., & Turiansky, G.W. (2008). Anetoderma: A case report and review of the literature. Cutis, 81(6), 501-506.

Persechino, S., Caperchi, C., Cortesi, G., Persechino, F., Raffa, S., Pucci, E., Tammaro, A., & Torrisi, M.R. (2011). Anetoderma: Evidence of the relationship with autoimmune disease and a possible role of macrophages in the etiopathogenesis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol, 24(4), 1075-1077.

Wang, K., Ross, N.A., & Saedi, N. (2015). Anetoderma treated with combined 595-nm pulsed-dye laser and 1550-nm non-ablative fractionated laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

Lee, S.M., Kim, Y.J., & Chang, S.E. (2012). Pinhole carbon dioxide laser treatment of secondary anetoderma associated with juvenile xanthogranuloma. Dermatol Surg, 38(10), 1741-1743.

Cho, S., Jung, J.Y., & Lee, J.H. (2012). Treatment of anetoderma occurring after resolution of Stevens-Johnson syndrome using an ablative 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser. Dermatol Surg, 38(4), 677-679.