CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

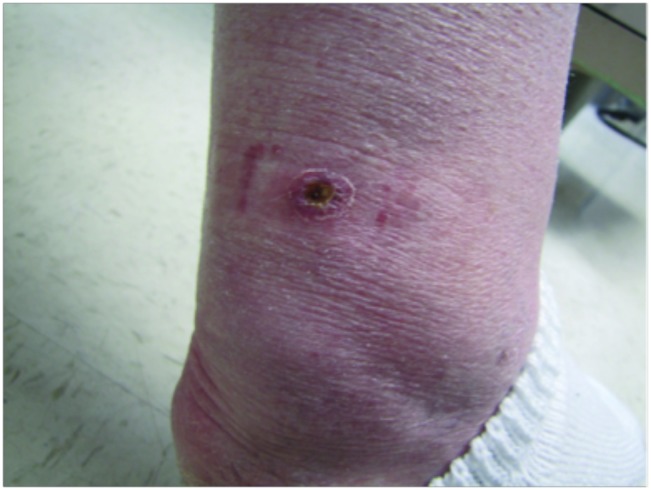

Erythema Induratum caused by Mycobacterium chelonei

DISCUSSION:

Erythema induratum (EI) was first described in 1855 by Bazin, prior to the identification of tuberculids. Although initially linked to pulmonary tuberculosis, there has been considerable debate regarding the role of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in EI’s pathogenesis. In the early 1900s, Whitfield and Galloway distinguished cases of EI not related to *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* infection, categorizing them as a separate clinical entity. Four decades later, Montgomery proposed the term nodular vasculitis to describe cases of EI lacking evidence of tuberculin origin. Despite the recent isolation of mycobacterial DNA from EI biopsies using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), many clinicians still use EI and nodular vasculitis interchangeably, regardless of etiology. Today, EI cases are most common in populations with a higher incidence of tuberculosis.

Clinically, EI presents with tender, violaceous nodules and plaques, primarily affecting the posterior lower legs of adolescent or perimenopausal women. The lesions often ulcerate and drain, with spontaneous resolution typically occurring within a few months, leading to post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and atrophic scarring. EI tends to have a chronic, recurrent course, with lesions reappearing every 3 to 4 months over many years. Histopathological examination reveals predominant lobular panniculitis with granulomatous inflammation, often accompanied by neutrophilic vasculitis affecting small and medium-sized vessels. Necrosis of fat lobule adipocytes may also occur, sometimes resulting in palisading granulomas.

Despite the prevailing view supporting the tuberculous origin of EI, other potential etiopathogenic factors have been suggested. Previous reports have linked EI with infections from Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, and viral infections such as Hepatitis C and B. Additionally, some cases have been associated with autoimmune diseases and propylthiouracil therapy. A recent study explored the possibility of atypical mycobacteria causing EI but did not successfully isolate atypical species, including Mycobacterium chelonei.

Mycobacterium chelonei is a rapidly growing atypical mycobacterium classified in Runyon group IV. Originally isolated from the sea turtle Chelona corticata, it is found widely in the environment, including soil and water. Cultures at 25 to 40°C produce nonpigmented colonies with rough or smooth surfaces. Although rare, Mycobacterium chelonei can cause disseminated disease in immunosuppressed individuals and localized infections following surgical procedures or trauma. In these cases, it often remains localized due to a sufficiently strong cell-mediated immune response. Treatment of Mycobacterium chelonei infections is challenging due to its resistance to standard antibiotics. While clarithromycin has shown effectiveness against all isolates in vitro, monotherapy is not recommended due to rapid resistance development. In this case, the authors chose to supplement 500 mg of clarithromycin twice daily with 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily, which is effective against 25% of Mycobacterium chelonei isolates. Other antibiotics that may be effective include tobramycin, amikacin, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin.

TREATMENT:

500mg clarithromycin twice daily and 100mg doxycycline twice daily with resolution after four months of therapy.

REFERENCES:

Bazin, E. (1861). Theoriques et Cliniques sur la Scrofula (2nd ed.). Paris: Dalahaye.

Sharon, V., Goodarzi, H., Chambers, C. J., et al. (2010). Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatology Online Journal, 16(4), 1.

Whitfield, A. (1901). On the nature of the disease known as erythema induratum scrofulosorum. American Journal of Medical Sciences, 122, 828–834.

Whitfield, A. (1905). A further contribution to our knowledge of erythema induratum. British Journal of Dermatology, 15, 241–247.

Galloway, J. (1913). Case of erythema induratum giving no evidence of tuberculosis. British Journal of Dermatology, 25, 217–225.

Montgomery, H., O’Leary, P. A., & Barker, N. W. (1945). Nodular vascular diseases of the legs: Erythema induratum and allied conditions. JAMA, 128, 335–345.

Gilchrist, H., & Patterson, J. W. (2010). Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): Diagnosis and management. Dermatologic Therapy, 23, 320–327. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01331.x

Mascaro, J. M., Jr., & Baselga, E. (2008). Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatologic Clinics, 26, 439–445. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.04.008

Segura, S., Pujol, R. M., Trindade, F., & Requena, L. (2008). Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: A histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 59, 839–851. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.017

Schneider, J. W., & Jordan, H. F. (1997). The histopathologic spectrum of erythema induratum of Bazin. American Journal of Dermatopathology, 19, 323–333. doi:10.1097/00000372-199710000-00004

Wolf, D., Ben-Yehuda, A., Okon, E., et al. (1992). Nodular vasculitis associated with propylthiouracil therapy. Cutis, 49, 253–255.

Bayer-Garner, I. B., Cox, M. D., Scott, M. A., & Smoller, B. R. (2005). Mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis are not present in erythema induratum/nodular vasculitis: A case series and literature review of the clinical and histologic findings. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology, 32, 220–226. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00272.x

Vemulapalli, R. K., Cantey, J. R., Steed, L. L., et al. (2001). Emergence of resistance to clarithromycin during treatment of disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection: Case report and literature review. Journal of Infection, 43, 163–168. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(01)00157-6

Halpern, J., Biswas, A., Cadwgan, A., & Tan, B. B. (2010). Disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection in an immunocompetent host. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 35, 269–271. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03568.x

Terry, S., Timothy, N. H., Zurlo, J. J., & Manders, E. K. (2001). Mycobacterium chelonae: Nonhealing leg ulcers treated successfully with an oral antibiotic. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 14, 457–461.

Tebas, P., Sultan, F., Wallace, R. Jr, & Fraser, V. (1995). Rapid development of resistance to clarithromycin following monotherapy for disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection in a heart transplant patient. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 20, 443–444. doi:10.1093/cid/20.2.443

Forslund, T., Rummukainen, M., Kousa, M., et al. (1995). Disseminated cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, amyloidosis, and renal failure. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 10, 1234–1236. doi:10.1093/ndt/10.8.1234

Wallace, R. Jr, Brown, B. A., & Onyi, G. O. (1992). Skin, soft tissue, and bone infections due to Mycobacterium chelonae: Importance of prior corticosteroid therapy, frequency of disseminated infections, and resistance to oral antimicrobials other than clarithromycin. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 166, 405–412. doi:10.1093/infdis/166.2.405

Iseman, M. D. (1999). Group IV Rapid growing mycobacteria. In Yu, V. I., Merigan, T. C. Jr, & Barriere, S. L. (Eds.), Antimicrobial Therapy and Vaccines (pp. 494–497). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.