CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

Primary Cutaneous Small/Medium Pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder

DISCUSSION:

This case represents an atypical T-cell proliferation consistent with primary cutaneous small/medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder formerly, primary cutaneous small/medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma.

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (CLs) are a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative neoplasms with lymphocytic proliferation limited to the skin without involvement of lymph nodes, bone marrow, or viscera at the time of diagnosis. Approximately seventy-five percent of CLs originate from mature T-lymphocytes, otherwise known as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). They tend to show considerable variation in clinical appearance, histologic appearance, immunophenotyping, as well as prognosis. Some common examples include, but are not limited to mycosis fungoides (MF), Sézary syndrome, and cutaneous CD30+ T- cell lymphoproliferative disorders. CTCL’s may present typically with multiple lesions, but some of the more rare types present with solitary lesions. These solitary lesions can run a relatively indolent course, but often pose diagnostic challenges. One of these entities is small/medium pleomorphic CD4+ T-cell lymphoma.

Interestingly, according to the prior 2005 World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (WHO-EORTC) classification, CD4 + primary cutaneous small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (PCSM- TCL) was listed as a provisional entity of CTCLs. However, the updated 2016 WHO classification, a revision of the 2008 WHO classification, also keeps PCSM-TCL as a provisional entity but renames it Primary Cutaneous CD4+ Small/Medium T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder (PCSM-LPD) to reflect the uncertain malignant potential as it is considered a limited clonal reactive response to an unknown stimulus as opposed to an overt lymphoma.

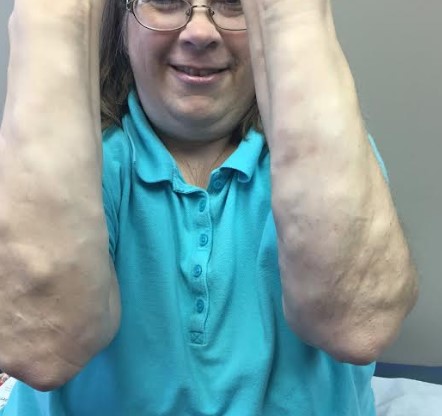

PCSM-LPD is a rare and somewhat controversial type of lymphoproliferative disorder that characteristically presents as a solitary plaque, nodule, or tumor most commonly on the face, neck or upper trunk in older patients. It generally runs an indolent course with a favorable prognosis with a 5-year survival of about 80%. There have been reports of aggressive, systemic disease. Those with rapidly evolving tumors, a high proliferation index and few admixed CD8+ T cells have been reported to be at risk for an even more aggressive clinical course. Some theorize that this spectrum of disease behavior suggests the consideration that this entity may actually be multiple diseases with shared clinicopathologic features rather than a singular disease process with a variety of behaviors.

Histologically PCSM-LPD has dense, diffuse, or nodular infiltrates in the dermis with a tendency to invade the subcutis. A predominance of CD4 + small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cells with a small proportion (less than 30%) of large pleomorphic cells may be present as well as focal epidermotropism. The proliferative rate is generally low. In most cases, a considerable admixture with reactive CD-8+ T-cells, B-cells, plasma cells & histiocytes are observed. Immunophenotyping demonstrates CD3+, CD4+, CD8- and CD30- neoplastic cells. Cases with a CD3+, CD4-, CD8+ phenotype usually have a more aggressive clinical course similar to that of primary cutaneous CD-8 + aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.

Despite being a an uncommon yet worrisome lymphoproliferative disorder, PCSM-LPD is a frequent diagnostic consideration in cutaneous biopsies with a dense lymphoid infiltrate, because it shows overlapping features with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma or lymphocytoma cutis) and a variety of other primary cutaneous and systemic lymphomas such as MF, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL), and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Therefore, distinguishing PCSM-LPD from other lymphoid disorders is imperative for determining patient prognosis and treatment options. Also, given the fact that precise clinicopathologic features of PCSM-LPD are not yet well established, further studies are needed to define the precise diagnosis and optimal treatment. Further work-up including immunohistochemical staining, special stains, and genetic testing are warranted to more confidently secure a diagnosis.

Furthermore, it is often quite difficult or even impossible clinically and histologically to differentiate between PCSM-LPD and T-cell pseudo lymphoma as two separate entities. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma refers to a heterogeneous group of benign reactive T-cell or B-cell lymphoproliferative processes of diverse causes that simulate cutaneous lymphomas clinically and histologically. Both present with a solitary plaque or nodule, and they both may stain for PD-1. Demonstration of an aberrant T-cell phenotype and clonality has been considered helpful in differentiating PCSM-LPD from pseudo-T-cell lymphomas, but the reported clinicopathologic features of these two entities really have considerable overlap. In addition, not all cases of PCSM-LPDs are monoclonal. On the other hand, T-cell pseudolymphoma is usually polyclonal and lacks an aberrant immunophenotype. However, T-cell pseudolymphoma has also occasionally demonstrated a monoclonal phenotype. Additionally, some evidence suggests that pseudolymphomas may progress to cutaneous lymphoma due to persistent antigenic stimulation. The lines between PCSM- TCL and T-cell pseudolymphoma may be blurred with little to no prognostic value.

Given the new WHO guidelines and the indolent nature of PCSM-LPD, less aggressive treatments are now preferred. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for solitary lesions. However, spontaneous resolution after biopsy has been reported. In cases with recurrence or with multiple lesions, radiation or chemotherapy has been used with success. In most cases, toxic treatment should be avoided and staging evaluation is not necessary.

In our case, given the size of the lesion, young age of the patient, and uncertain nature of the infiltrate, the patient was referred to a Pediatric Hematologist/Oncologist where a further work-up was performed. This included FISH testing for TCR translocations, which may be seen in a more aggressive peripheral T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, all of which were negative and supported the diagnosis of PCSM-LPD. Fortunately, at the post-biopsy dermatology visit, the patient and her mom reported that the lesion was shrinking. Since the lesion was located in a cosmetically sensitive area on the face, hematology/oncology recommended observation and continued surveillance. They also recommended considering radiation therapy only if the lesion failed to self-resolve in the next 3-6 months or the lesion enlarged, lymph nodes are palpated, or the behavior of the site changed in any way. Intralesional steroids were also posed to the patient as an option however, they have not chosen that treatment option as of yet.

TREATMENT:

Observation including skin exams every three months. Localized radiation therapy or intralesional steroids will be considered if the lesion fails to resolve.

REFERENCES:

Ally M and Robson A. A Review of the Solitary Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2014; 10: 1-10.

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC Classification for Cutaneous Lymphomas. Blood 2005;105(10):3768–3785.

Swerdlow, S. and Campo E. Review Series: The Updated WHO Classification of Hematologic Malignancies: The 2016 Revision of the World Health Organization Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms. Blood Journal 2017. 11(3).

Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, et al. The 2008 WHO Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms and Beyond: Evolving Concepts and Practical Applications. Blood 2011;117:5019–5032.

Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Olek-Hrab K, Ruckemann-Dziurdzińska K. Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas: Diagnosis and Treatment. Advances in Dermatology and Allergy. 2015;32(5):368-383.

Keeling B, Gavino A, Admirand J et al. Primary Cutaneous CD4-Positive Small/Medium-Sized Pleomorphic T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2017 Nov;44(11):944-947.

Bergman R. Pseudolymphoma and Cutaneous Lymphoma: Facts and Controversies. Clinical Dermatology. 2010 Sep-Oct;28(5):568-74.

Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology, 3rd Ed. Spain: Elsevier, 2012: 2017-2034.

Maurelli M, Colato C, and Gisondi P et al. Primary Cutaneous CD4 + Small-/Medium-Pleomorphic T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder: A Case Series. Journal of Cuntaneous Medical Surgery. 2017; 21(6): 502-506.

James E, Sokhn JG, Gibson JF, Carlson K, Subtil A, Girardi M, Wilson LD, Foss F. CD4 + Primary Cutaneous Small/Medium-Sized Pleomorphic T-cell Lymphoma: A Retrospective Case Series and Review of Literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015 Apr;56(4):951-7.

Lan T, Brown N, Hristov A. Controversies and Considerations in the Diagnosis of Primary Cutaneous CD4+ Small/Medium T-Cell Lymphoma. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2014; 138: 1307-17.

Grogg KL, Jung S, Erickson LA, et al. Primary Cutaneous CD4-Positive Small/Medium-Sized Pleomorphic T-Cell Lymphoma: A Clonal T-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder with Indolent Behavior. Modern Pathology. 2008;21:708–715.

Williams VL, Torres-Cabala CA, Duvic M. Primary Cutaneous Small-to Medium-Sized CD4 + Pleomorphic T-Cell Lymphoma: A Retrospective Case Series and Review of the Provisional Cutaneous Lymphoma Category. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2011;12:389–401.

Beltraminelli H, Leinweber B, Kerl H, et al. Primary Cutaneous CD4 + Small-/Medium-Sized Pleomorphic T-Cell Lymphoma: A Cutaneous Nodular Proliferation of Pleomorphic T Lymphocytes of Undetermined Significance. A Study of 136 Cases. American Journal of Dermatopathology. 2009;31:317–322.

Maurelli M, Colato C, and Gisondi P et al. Primary Cutaneous CD4 + Small-/Medium-Sized T-Cell Lymphomas: A Heterogenous Group of Tumors With Different Clinicopathologic Features and Outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008; 26(20): 3364-71