CORRECT DIAGNOSIS:

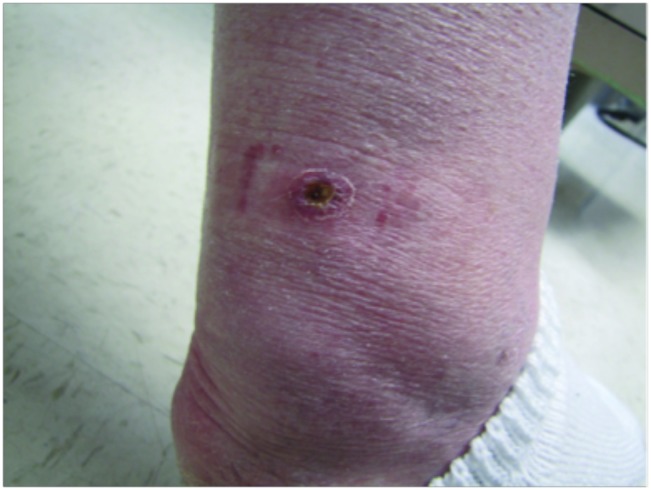

PCALCL due to clinical presentation and histological findings

DISCUSSION:

This case demonstrates an atypical CD30 positive lymphoid infiltrate; however, the exact diagnosis was inconclusive. The differential diagnosis included primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PCALCL), lymphomatosis papulosis (Lyp), cutaneous metastasis from a nodal or systemic ALCL, CD30 positive transformed mycosis fungoides, rare types of CTCL that can occasionally show positivity of CD30, and reactive processes such as drug reactions, arthropod bites and viral infections (1, 2). Based on our patient’s history, clinical presentation, and histology findings, our patient likely had a PCALCL.

PCALCL accounts for approximately 12% of all CTCLs. Clinically, it presents with an ulcerated, rapidly growing solitary tumor or grouped nodules. PCALCL is most common in the 6th decade of life, and twice as common in males than females. It tends to appear on the head, neck, and extremities. Histologically, the tumor is composed of large, anaplastic, pleomorphic lymphocytes with irregular nuclei and abundant cytoplasm arranged in sheets infiltrating the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Over 75% of lymphocytes stain positive for CD30. They also commonly express a CD4+ T-cell phenotype, with less than 5% expressing a CD8 phenotype. Expression of MUM1/IRF4 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1/interferon regulatory factor 4) is seen in almost all cases and there is variable loss of CD2, CD3, and/or CD5. Some cases are positive for ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) or EMA (epithelial membrane antigen). These cases suggest that chromosomal translocation of t(2;5) is likely, and further workup for systemic or nodal ALCL should be performed. Standard treatment for PCALCL is excision of the entire lesion. If the lesion is too large to be excised or is excised with involved margins, radiotherapy should be performed in conjunction (1, 2, 3). In up to 42% of cases, the lesion may partially or completely regress, similar to Lyp. Recurrences, however, are common and treatment is necessary for remission (4,5). The prognosis is typically favorable, with a 5-year survival rate between 76% and 96% (6).

PCALCL and Lyp are very similar in regards to clinical and histologic appearance, often making a distinction between the two difficult. Lyp is most commonly categorized as a low-grade variant of CTCL due to its CD30 positivity and presence of abnormal T cells. It has five distinct (A-E) histological subtypes, and presents clinically as asymptomatic localized clusters or disseminated erythematous to brown papules and/or nodules, that spontaneously regress within weeks to months.

In any CD30 positive lymphoid infiltrate case, if the patient has a history of MF, the possibility of large cell transformation of MF must be considered. Large-cell transformation is diagnosed when greater than 25% of the lymphoid infiltrate contains CD30+/- large cells (7). This diagnosis is associated with a very poor prognosis.

CD30 positive lymphoid infiltrates can also occur in many non-neoplastic skin conditions as part of a reactive activated T-cell response. CD30+ lymphoid infiltrates have been described in drug reactions (8, 9), atopic dermatitis (10), pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformic acuta (PLEVA) (11), keratoacanthomas (12) and many infections including tuberculosis (13) multiple viruses (14), and arthopod assaults (15).

TREATMENT:

Treatment included wide local excision with resulting clear margins found on histopathology. The patient was referred to oncology for further evaluation in order to rule out a systemic or node-based lymphoma. All additional testing, including PET CT, was negative. The patient continues to do well several years later and still is routinely followed by oncology.

REFERENCES:

1. Kempf W. Cutaneous CD30-Positive Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Surg Pathol Clin. 2014;7(2):203-28.

2. Willemze R. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, editors. Dermatology. 2. Third ed. China: Elsevier; 2012. p. 2017-36.

3. Kempf W. A new era for cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(1):22-35.

4. Vergier B, Beylot-Barry M, Pulford K, Michel P, Bosq J, de Muret A, et al. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic and prognostic features of CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 65 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(10):1192-202.

5. Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, Cozzio A, Ortiz-Romero PL, Bagot M, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(15):4024-35.

6. Benner MF, Willemze R. Applicability and prognostic value of the new TNM classification system in 135 patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1399-404.

7. Salhany KE, Cousar JB, Greer JP, Casey TT, Fields JP, Collins RD. Transformation of cutaneous T cell lymphoma to large cell lymphoma. A clinicopathologic and immunologic study. Am J Pathol. 1988;132(2):265-77.

8. Chen YC, Wu YH. Linear Folliculotropic CD30-Positive Lymphomatoid Drug Reaction. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(5):e62-e5.

9. Saeed SA, Bazza M, Zaman M, Ryatt KS. Cefuroxime induced lymphomatoid hypersensitivity reaction. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76(899):577-9.

10. Piletta PA, Wirth S, Hommel L, Saurat JH, Hauser C. Circulating skin-homing T cells in atopic dermatitis. Selective up-regulation of HLA-DR, interleukin-2R, and CD30 and decrease after combined UV-A and UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(10):1171-6.